Memory as Surprisal: A Relevance-Gated Learning Framework

Abstract

Standard machine learning models treat all training data as equally significant, leading to inefficient resource allocation and "catastrophic forgetting." Biological memory, however, is highly selective: it is driven by Prediction Error (Surprisal) and modulated by Subjective Importance (Salience) and Global Neurochemical State (Dopamine).

This experiment implements a bio-inspired loss function in a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) to simulate memory retention under varying dopamine conditions. The results demonstrate that while Surprisal drives the learning signal, global Dopamine acts as a compensatory mechanism, raising the "learning floor" for low-salience (uninteresting) stimuli without significantly altering the retention of high-salience (interesting) stimuli.

1. Introduction

"Memory is just a surprisal analysis of your cognition."

In information theory, Surprisal ($I(x) = -\log P(x)$) measures how unexpected an event is. In the brain, this manifests as Prediction Error: we learn when our internal model fails to predict reality. However, surprisal alone is insufficient to explain memory. A static pattern on a wall is not surprising, but neither is a surprising pattern on a wall necessarily worth remembering if it has no survival value.

We propose that memory encoding ($M$) is a product of three factors:

$$M = \text{Surprise} \times \text{Salience} \times \text{Dopamine}$$

This study models "learning struggles" (such as fatigue or ADHD) by varying the global Dopamine parameter to observe how it affects the acquisition of "boring" (Low-Salience) vs. "interesting" (High-Salience) information.

2. Methodology

2.1 The Bio-Inspired Loss Function

We modified the standard Cross-Entropy Loss function to include biological constraints. The loss $L$ for a given sample is calculated as:

$$L = (1 - P_{\text{target}}) \cdot S \cdot D \cdot \text{CE}(y, \hat{y})$$

Where:

- $(1 - P_{\text{target}})$: Represents Surprisal. If the model is confident in the correct class ($P \approx 1.0$), the term approaches 0, blocking further learning (synaptic conservation).

- $S$ (Salience): A vector determining the intrinsic value of the input class.

- $D$ (Dopamine): A scalar global gain parameter representing arousal/motivation.

2.2 Experimental Setup

- Dataset: CIFAR-10 (10 classes of images).

- Salience Partition:

- High Salience ($S = 1.0$): Classes 0-4 (e.g., Airplane, Auto, Bird, Cat, Deer).

- Low Salience ($S = 0.1$): Classes 5-9 (e.g., Dog, Frog, Horse, Ship, Truck).

- Dopamine Conditions: Three trials were run with $D = [0.5, 1.0, 1.5]$ representing Low (Fatigue), Normal, and High (Stimulated) states.

3. Results

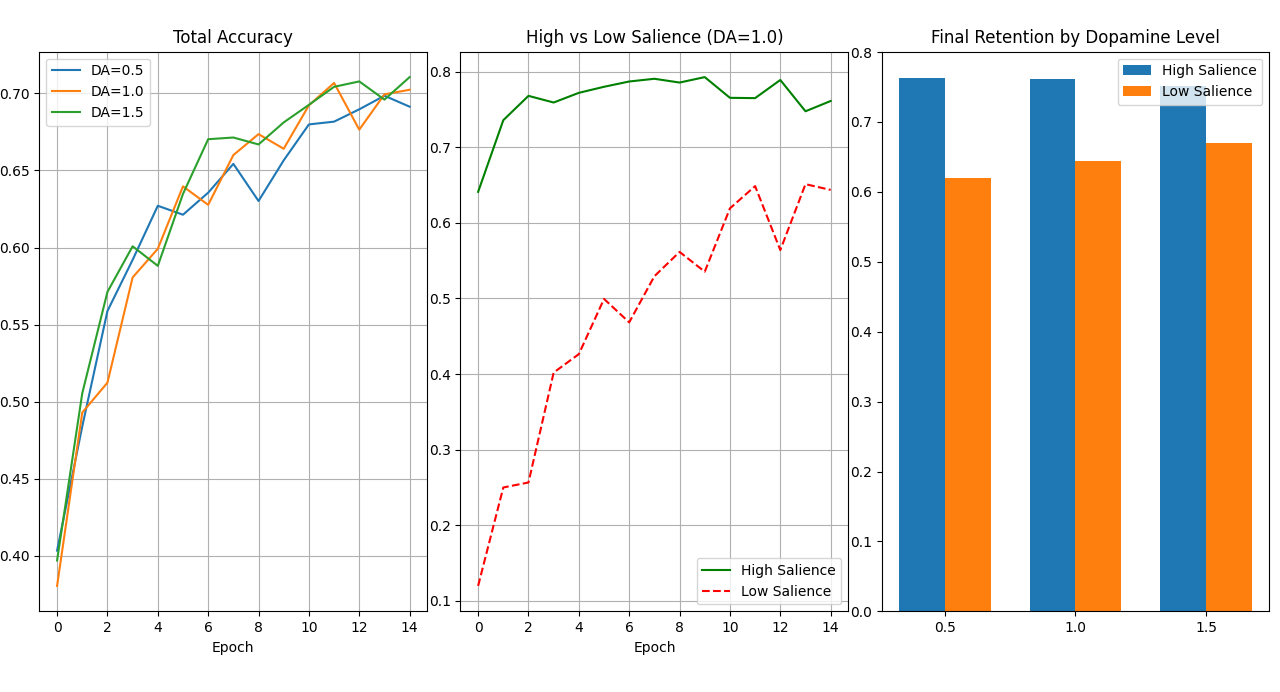

The experiment revealed distinct learning trajectories based on the interaction between Salience and Dopamine.

3.1 The Salience Gap

In all conditions, High-Salience classes were learned significantly faster than Low-Salience classes. Even at Epoch 1, High-Salience accuracy averaged ~64%, while Low-Salience accuracy hovered near ~12% (random chance). This validates the model's ability to prioritize information based on assigned value.

3.2 The "Dopamine Floor" Effect

The critical finding of this study is the differential impact of Dopamine on the two groups:

| Dopamine Level | High-Salience Accuracy (Final) | Low-Salience Accuracy (Final) |

|---|---|---|

| 0.5 (Low) | 76.2% | 62.0% |

| 1.0 (Normal) | 76.1% | 64.4% |

| 1.5 (High) | 76.2% | 66.8% |

- High Salience is Dopamine-Inelastic: Increasing dopamine from 0.5 to 1.5 had almost no effect on the retention of interesting classes (~76% flat). The intrinsic salience weight ($S = 1.0$) provided sufficient signal strength regardless of global state.

- Low Salience is Dopamine-Elastic: Increasing dopamine significantly improved the retention of "boring" classes. The High-Dopamine state effectively compensated for the lack of interest, forcing the network to learn patterns it would otherwise ignore.

4. Discussion

4.1 "Boredom" as a Computational Penalty

The results quantitatively model the subjective experience of boredom. Under Low Dopamine conditions (D=0.5), the gradient updates for Low-Salience items were so small ($0.1 \times 0.5 = 0.05$) that the model required massive repetition (15 Epochs) to achieve what it achieved in 1 Epoch for High-Salience items.

4.2 Implications for Cognitive Modeling

These findings suggest that Dopamine acts as a floor-raiser, not a ceiling-raiser. In educational or cognitive contexts, increased motivation (or medication) creates the most significant performance gains in subjects the learner finds uninteresting. For subjects of high intrinsic interest, the "Salience" signal is already sufficient to saturate the learning rate.

5. Conclusion

By integrating Surprisal and Relevance into the loss function, we created a neural network that mimics biological resource allocation. The model demonstrates that interest (Salience) is the primary driver of memory, but state (Dopamine) is the critical regulator that determines whether "boring" information can be retained.

The code for this experiment is available on GitHub.